Small Kingdom, Big plastic

Tonga is situated at the heart of the South Pacific, to the West of the international date line; it’s one of the first countries to see the sun rise each day.

Race for Water spent eight days in Tonga from 7 to 15 December 2018. Anne-Laure Le Duff, second in commande, shares with us the results of this stopover.

This is a country with a unique history. At the start, there were islands where each community had relations with its neighbours that could be peaceful and warlike at times. In 1773, a certain James Cook dropped anchor in one of the archipelagos there and the reception was so friendly and welcoming, rather than murderous!, that he named them the “Friendly Islands”. In 1845, King Georges Tupou I managed to unite the 170 islands and islets spread across three island groups, Ha’apai, Vava’u and Tongatapu, in one kingdom. The British later cut their official ties and Tonga became independent in 1970. In 2010, the Tongans added another line to their rich history, establishing a constitutional monarchy. There is still a deep attachment for its royal family there, as evidenced by the huge crowds gathered to witness the arrival of Princess Salote Mafileo Pilolevu Tuita and her daughter Frederica Fatafehi Lapaha Tuita Filipe at Race for Water’s welcoming ceremony. Tongan society is tinged with the secular traditions governing the community and there is a deep respect for hierarchy in both family and institutional circles.

Here, like elsewhere in the world, the way of life has changed dramatically and not all of its westernisation and the associated ‘progress’ has been for the better. Indeed, the population is becoming addicted to imported products and the shells of Japanese cars are piling up. On the island of Tongatapu, solely metals are recycled by GIO, the kingdom’s only permanent recycling company, whilst the Tapuhia rubbish tip collects all the solid industrial and household waste. Landfill is an accepted method of disposal in the islands and more than half of the volume of the rubbish is taken up by… plastic.

Once again, the lack of market value in this material means that the ecological deficit is widening, making the man-plastic relationship unilateral: no recycling, no compactor to put it into storage, no exporting, no second life for these thousands of objects from daily life. And yet, the organisation of rubbish collections is in place and other solutions have been envisaged for aluminium cans. In fact, the villages and communities even call upon the services of groups of women, who are responsible for sorting the waste and then redistributing the money earned among their respective communities. Only recently has the billing for the roads been included in that of electricity, so the desire is there among citizens but the infrastructure for recycling and recovering PET and the like is sadly lacking. In 2013, Waste Authority Ltd implemented a tax on the importing of plastic, at the expense of the importer, at a rate of 10% of the customs value, which is a first step.

One of the government’s main approaches is education and within this context Mrs Ta’hiri F. Hokafonu is absolutely sure that “Education is key”. Heading the Department of Biodiversity, the integration of the ocean and the management of ecosystems, she knows about the ecological problems associated with plastic and its lack of processing only too well. The government and citizen-based initiatives are effective and diversified and they are backed by non-governmental organisations and private companies. This ranges from the broadcasting of programmes to educate and raise awareness about the environment on all the different audio-visual media and learn about composting, to signs along the roads prohibiting inhabitants and visitors from disposing of waste, to the “Citizen Program”. The latter comprises a collection of the waste in marine protected areas by students from local schools and colleges on the basis of “Learn (typology of waste), Share (awareness) and Act (collect)”; a “National Clean-Up” carried out 3 times a year by the local teams; a “Clean-Up Competition” 4 times a year organised for the island’s different communities and an annual “Coastal Clean Up” grouping together 27 villages. During the latter, of the 280 tonnes of waste collected, over half is recyclable. During the visits aboard the boat, some people were surprised to learn that plastic breaks down into microparticles and then nanoparticles that end up either at the bottom of the oceans, on the beaches or on their plate, making it impossible to clean the oceans and hence imperative that we change how we behave on land.

The Kingdom of Tonga, like twenty or so other Pacific states, benefits from the support and aid of the main environmental protagonist, the “Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme” (SPREP), which works with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (UICN) to provide assistance with technical matters and decision-making in a bid to manage Tonga’s biodiversity and energy transition.

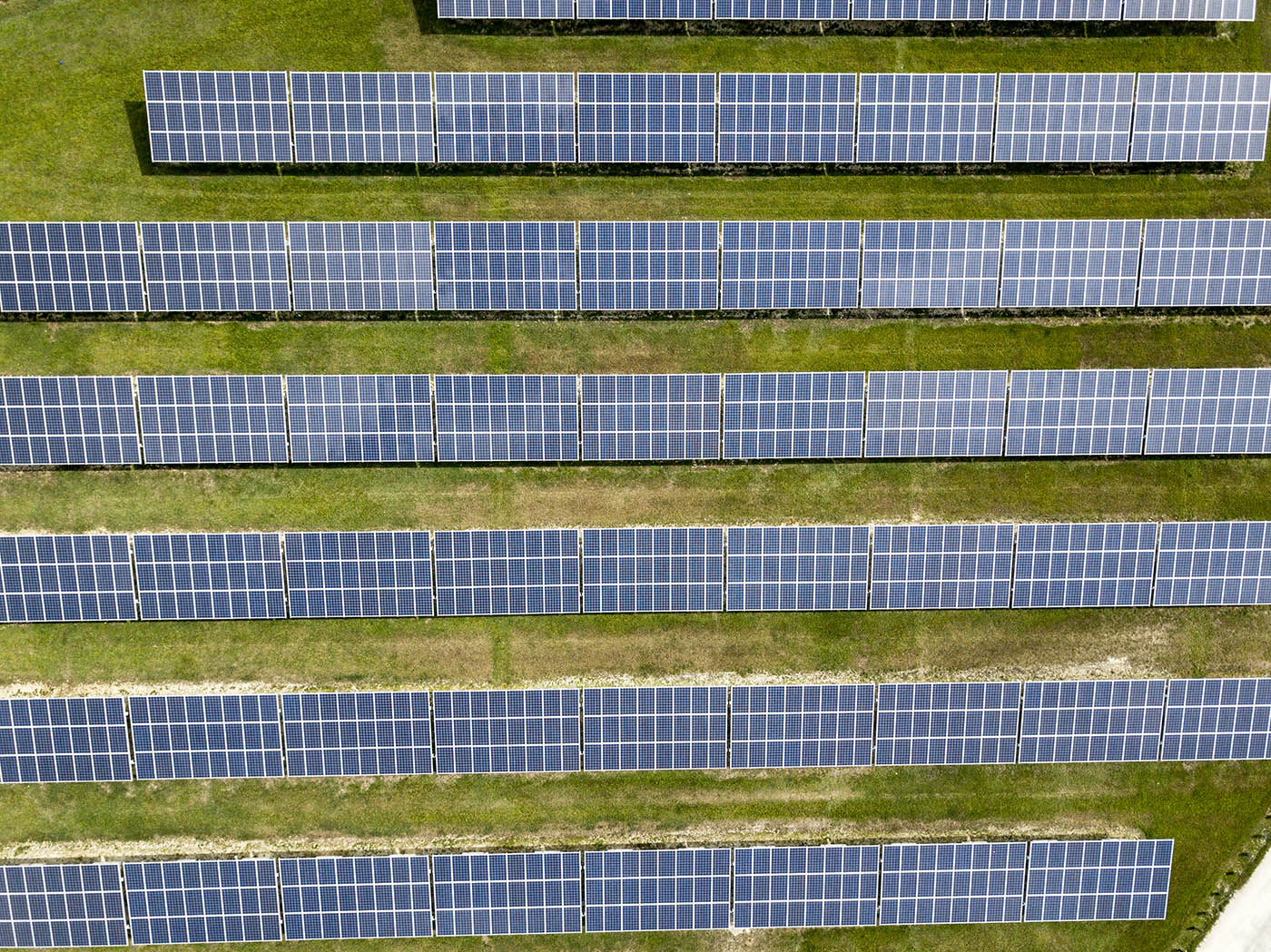

Multiple international funds have been allocated to finance the installation of a site for wind turbines, solar energy and storage (batteries). It’s an ambitious project, aiming for 50% renewable energies between now and 2020 and 100% between now and 2035 by integrating the Waste To Energy scheme.

We had the opportunity to visit the Maama Mai solar farm, which boasts 5,750 solar panels adjoining 8 diesel generators. 80% of the total energy produced is consumed by businesses, they themselves representing 20% of consumers… Tonga Power Ltd has a substantial challenge ahead of it to find technologies geared around the needs of the archipelagos (population and businesses) and to find locations to install 3 wind farm sites and 2 energy storage sites. The use of biomass, including waste, is an integral part of their project. In fact, Waste to Energy would represent stable electricity production, whilst wind turbine and solar energy would serve as a ‘buffer’ energy solution. Time is short and current production is only just able to satisfy demand. Meantime, the rubbish tip is filling up and within 5 years it will have reached full capacity.

Meanwhile, creativity is doing its work right across the island, with tyres transformed into flower pots strewn around houses and plastic bottles making original planters. This kingdom with its flamboyant biodiversity, rich in over 170 marine species and an abundance of endemic birds must, like so many others, face up to the climate change and societal change, which is impacting the world at the speed of light. The desire for change is there, but there is too little funding and too few projects that are honed or in the process of being completed given the ecological and economic imperatives of this little country. The government plays a key role and it is not alone; the population must take action and take on these challenges with gusto. One of the four Tongan values is “Tauhi vaha’a”, which means loyalty and commitment. We can easily transpose them to the current situation and make them our own: loyalty to a nourishing nature and a commitment to a future that is more respectful of the Living.”

Alu a Tonga

Goodbye Tonga

Anne-Laure Le Duff

Video review of the stopover in Tonga

Thank you to all the local supporters for their commitment alongside us :